Hoover in Newberg: A Quiet Legacy

By: Aidan Arthur

<Newberg, Ore.> It takes five minutes to walk from the Hoover-Minthorn House Museum in Newberg to the Hoover Academic Building at George Fox University (GFU). Herbert Hoover was once listed by TIME as one of the nation’s most “forgettable” presidents, yet this small town seems to remember him well enough.

However, even Newberg’s claim to this seemingly uninteresting historical figure is somewhat tenuous. In a world that has been questioning what historical figures should be honored, another question arises: do this town and university deserve whatever honor Hoover’s name bestows?

Hoover was born in Iowa but was taken in by his uncle and aunt, John and Laura Minthorn, after he was orphaned at nine years old. A devout Quaker family like his own, they lived across the country in Newberg, a town of around 200 people. John Minthorn was a doctor and also the superintendent at Friends Pacific Academy, which would later become GFU.

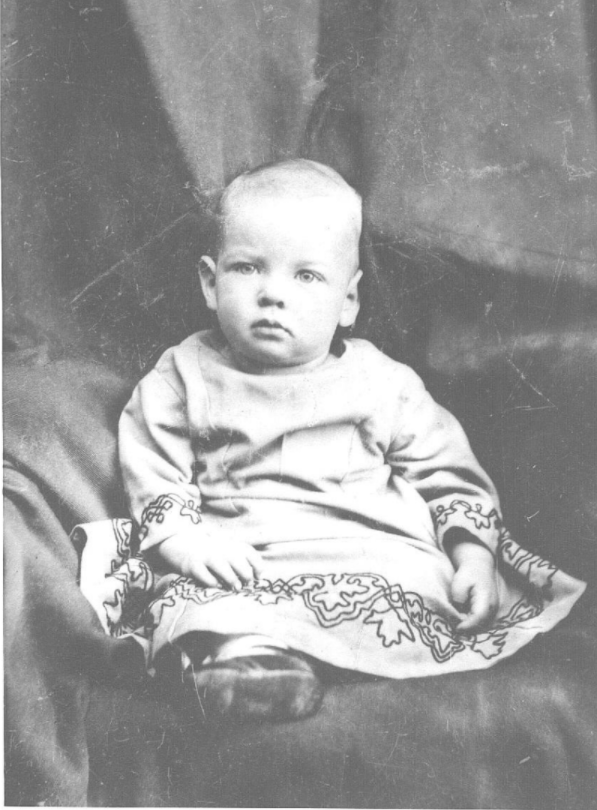

Hoover at age 3. Photo courtesy: Hoover-Minthorn House Museum

“[Minthorn] offered for him to come here and help out with chores and he could go to school for free,” said Nina Dahl, director of the Hoover-Minthorn House Museum. This historical site is the house Hoover lived in during his time in Newberg, refurbished with period furniture and decorations.

The facts of Hoover’s time in Newberg cast doubt on the university’s association with him. He only lived here from the ages of eleven to fourteen before moving to Salem, and at the time what is now GFU was a small academy—a totally different institution, despite their close historical connection. Additionally, his relationship with his uncle was strained.

Hoover would go on to Stanford University, which naturally became more of a factor in his later life than the Quaker academy he attended as an adolescent. Nevertheless, he maintained correspondence with college President Levi Pennington. In a letter about the commencement of Pacific College in 1941, he wrote, “If I still believe in the moral and spiritual foundations of civilization, [Friends Pacific Academy] is where it was implanted in me.”

Hoover’s years in Newberg may have been brief, but he eventually came to regard them as formative.

During and after World War I, Hoover found great success as head of the newly formed Food Administration. He managed to strike a balance between his opposition to excessive federal action and the need for strong leadership.

Hoover’s White House biography states that when his decision to give aid to Soviet Russia was questioned, he responded by saying, “Twenty million people are starving. Whatever their politics, they shall be fed!”

Yet Hoover’s presidency would be defined by a time when this cautious strategy failed him—the Great Depression, which began in 1928, the first year of his term.

In comparison to the New Deal policies of his successor, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hoover’s response was relatively inactive. This strategy was based on principles that limited federal involvement and encouraged private efforts to address problems, and his reticence is seen as having been partly to blame for the Depression’s persistence.

“No individual political leader could have solved [the Depression]...No matter what country you’re in, everybody always blames whoever’s leading the country at the time of an economic recession,” said Caitlin Corning, GFU history professor and chair of the Department of History and Politics.

“I don’t want to say that all of his policies were successful, but he was president at a particularly difficult time,” Corning said. “Traditional economic theory was not working out.”

Herbert Hoover. Photo courtesy: Getty Images

Though Hoover wasn’t able to solve the Depression, his presidency wasn’t the only part of his political career. In Hoover’s 90-year life, the presidency took up only four years, and they were some of the most difficult he could have been dealt.

Hoover is not counted among the greats of American history. Even beyond economic mismanagement, he had views on race that—though not extreme for the time—are nonetheless morally indefensible.

Senator Mark Hatfield said at the dedication of the Hoover Academic Building in 1977, “I don't think it's necessary to make him a saint or a hero; his actions speak for themselves." Though Hatfield’s words seem meant to lionize Hoover, his actions do tell a story. And despite all his failures, he’s not beyond redemption.

It takes five minutes to walk from the Hoover-Minthorn House Museum to the Hoover Academic Building. Neither is flashy. Neither is crammed with tourists eager to learn about the 31st president or to stand in awe of the great works of Herbert Hoover. They’re just buildings, a part of the scenery, nothing exceptional.

Maybe this is the legacy the man—and the town—deserve.

Hoover-Minthorn House Museum dedication day in 1955. Photo courtesy: Hoover-Minthorn House Museum